I recently co-presented a session titled Codify Your Environment with Terraform and Ansible at the inaugural Rubrik Forward Digital Summit. My demo used GitHub Actions to run a number of Ansible playbooks. The code is hosted at https://github.com/rfitzhugh/Forward-2020-Codify-Your-Environment. One of my main takeaways for those attending the session is that Continuous Integration (CI) tools like GitHub Actions can be used to test and run automation against your infrastructure fairly easily. Let’s take a look.

The GitHub Actions Flow

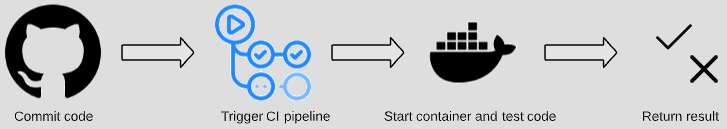

CI tools were created to make life easier for developers by allowing them to test changes to their code rapidly. Modern CI tools leverage cloud infrastructure and containers to run these tests when code is committed. A typical workflow looks something like this:

Normally, someone creates a branch on a Git repository, commits some changes, and opens a Pull Request. This alerts the repo owner(s) that there are proposed code changes. A pipeline is usually triggered when the pull request is opened to run tests against the new code. The test result is returned when completed, and is a major consideration as to whether or not the new code is merged. Another pipeline may be triggered after the pull request is merged, or at other points in the process. The timing for when pipelines run is specified in the CI pipeline configuration, and varies by project and need.

Rubrik Chief Technologist Chris Wahl wrote a snazzy blog post that demonstrates this workflow with Terraform. His post goes into greater detail on GitHub Actions than I will, so if you’re new to the tool then I recommend taking a moment to read his post before continuing.

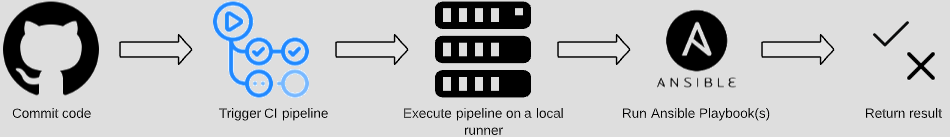

When it comes to using this process to execute Ansible Playbooks against your on-prem infrastructure, the process is slightly different. It looks like this:

The beginning is the same, up to where the CI pipeline is triggered to run. In this case, we only want the pipeline to run after a Pull Request is merged into the master branch. The master branch should be considered the source of truth for your infrastructure, and changes must never be made directly to the master branch. All modifications to the Playbooks in the repo will be proposed via Pull Request, reviewed, commented on and ultimately accepted or denied. Only after the PR is accepted and merged to master will the Ansible Playbook(s) be executed. This is an important concept to grasp as you certainly do not want to be making unintended changes due to a pipeline being run unexpectedly.

The other difference from the first example is that a local runner is used to execute the pipeline instead of a Docker container. This runner is installed in a Virtual Machine, in this case in our lab, so it has connectivity to all of the infrastructure that we’d like to automate. Instructions for adding a local runner to a repo and making it available to GitHub actions are located here: https://help.github.com/en/actions/hosting-your-own-runners/adding-self-hosted-runners. Notice the ominous “Warning: We recommend that you do not use self-hosted runners with public repositories.” This is indeed sound advice - some additional security considerations will be covered near the end of this post.

Configuring GitHub Actions for Automation

A basic GitHub Actions configuration file needs to contain three things:

- When to Run

- Where to Run

- What to Run

There are, of course, a bazillion different ways this can be configured. The examples below will focus on the Ansible workflow described above. A full configuration can be found here: https://github.com/rfitzhugh/Forward-2020-Codify-Your-Environment/blob/master/.github/workflows/run-playbooks.yml.

When to Run

For many CI pipelines, this will be when a Pull Request is opened, but as mentioned above, that won’t work for our case. We only want the pipeline to run after a Pull Request is merged (i.e. approved). Here’s what that configuration looks like:

on:

push:

branches:

- master

Do this

The “push” action is triggered when merging code into the master branch. The first time I tried to figure out how to set this configuration, I had trouble finding the correct keywords. I ended up digging around in issues and forums, and found this solution:

on:

pull_request:

branches: [ master ]

types: [closed]

Don’t do this

While this does execute a pipeline after a Pull Request is merged, it will also run the pipeline when the PR is simply closed. Closing the PR means no code was merged in, hence no changes, but it still results in the pipeline running when you wouldn’t expect it to. Hopefully this wouldn’t be a major problem since Ansible is idempotent, and the repo still matches the running state of your infrastructure. Still, stick with the first example. Do not use on: pull_request for your automation CI pipeline!

Where to Run

jobs:

run-playbooks:

runs-on: self-hosted

There is one job (“run-playbooks”) in this example, made up of one or more steps. This example instructs GitHub actions to execute the steps on your self-hosted runner. The main reason for this is the runner has connectivity to the infrastructure you’re attempting to automate. You also have the ability to pre-stage any necessary dependencies on the runner. This may be Ansible collections, Python modules, or other prerequisites.

What to Run

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Run Ansible Playbook

run: ansible-playbook your_playbook.yaml

Finally, the files from repo are checked out via Git, and the Ansible playbook is fired off. This can be repeated, as necessary, if there are multiple playbooks. If Ansible returns an error, the pipeline aborts and the repo owners will be notified that the pipeline failed. If you are running multiple playbooks, you may have a workflow that is partially complete. In this case, there is probably some clean-up to do. Revert things to their previous state, and troubleshoot the error that was returned before trying again.

Security Considerations

First, you are placing sensitive information about your environment in a Git repository. There is no reason I can think of to use a public repo for this. Private repos are now free on GitHub, so use that capability and keep prying eyes away from your carefully designed playbooks.

Second, whatever you put in your CI pipeline will be executed in your environment, on your local runner. This is why all Pull Requests should be reviewed by someone other than the original author. Have a second set of eyes review any proposed changes, and if possible, test thoroughly in a sandbox environment before proposing a Pull Request.

Third, rely on GitHub Secrets to store passwords, tokens, and other sensitive information. The configuration example above demonstrates how to use secrets associated with a repo, and inject them into environment variables on the local runner so Ansible can reference them. Keep in mind that some secrets may be displayed in your CI logs if you have verbose logging enabled, so use caution.

I’ve seen recommendations to build an “emergency off switch” that can abort automation workflows from running. This could be a firewall rule that blocks all communication to and from the local runner, or a script that immediately powers it off. An abort mechanism is worth considering as you increase your reliance on automation.

Wrap Up

Back in 2018 when I wrote my review of Network Programmability and Automation, one of my few complaints about the book was that it was light on how CI pipelines are used within an automation workflow. I hope this post was helpful in shedding some light on this topic. There are many different available tools and approaches to this, so you may end up with a different way of tackling this in your own environment. I’d love to hear how you’re managing automation, or if there is anything I can add to my approach to improve it. Hit me up any time on Twitter @NetworkBrouhaha.