My last post laid out several options for connecting to the cloud. In this post, I’ll dive into reliable connectivity to the cloud. In the real world, circuits drop, transceivers fail, and software bugs cause lockups or unexpected reboots. This is one of the fundamental tenants of working with technology. If you expect five nines of uptime, you must plan for component failures and unexpected outages.

When it comes to networking, reliability is typically achieved with redundancy and resiliency. Redundancy means two or more components (e.g. switches, routers, circuits) are in place to tolerate the failure of any single device. Resiliency means that the overall system continues to operate when a component failure occurs. This usually requires some configuration on the part of the operator to ensure an automated switchover occurs, and hopefully testing of every failure scenario to ensure that switchover works as expected. Having two of everything doesn’t provide any benefit if the redundant component doesn’t take over when the primary fails!

The rest of this post will focus on the specifics of reliable cloud connectivity, but it is important to consider that reliability is constructed in stages. I’m assuming that your existing network infrastructure is already reliable. If that is not the case, it won’t matter how awesome your cloud connectivity is. You must build upon a stable foundation.

Software Defined WAN (SD-WAN)

In my last post, I said that SD-WAN “may be the most exciting advancement in the world of networking in the past decade.” I’m referring to SD-WAN in general terms since there is a lot of vendor-specific secret sauce baked into the various offerings. With that in mind, here are the things that SD-WAN gets right when it comes to reliability:

- Redundancy is assumed. Reference architectures for SD-WAN assume there are at least two paths available for connectivity. This may be as simple as a primary internet circuit and an LTE connection for backup.

- Failover is automatic. SD-WAN devices constantly verify connectivity between the participating edge devices, as well as the health of that connection. When a connection goes down, traffic is automatically moved to another available connection. Even more impressively, if a connection is experiencing packet loss or high latency, traffic can be migrated to prevent a performance hit. With a traditional solution, this is a difficult problem to detect unless you are on top of your monitoring game.

SD-WAN is still gaining traction, but the technology is exciting. There are several other benefits in terms of security, manageability, monitoring, and automation. If you’re building a new solution, or looking to replace aging edge hardware, SD-WAN deserves a hard look. You can build a fast, fault tolerant connection to the cloud, and even replace legacy WAN technologies like MPLS. The most important thing to consider with cloud connectivity via SD-WAN is that your chosen vendor has supported software appliances in your cloud(s) of choice. Read through their cloud reference architecture to ensure they meet your requirements. Cloud-based SD-WAN appliances are software-based, so they will have bandwidth limitations that should be taken into account as well.

Dynamic Routing and Automated Failover

If you’re not in a position to roll out SD-WAN, you will need to use the tried-and-true networking technologies that have been around for decades. Dynamic routing is the primary tool used to provide reliable network connectivity and facilitate traffic failover during an outage. There are several dynamic routing protocols that can achieve this, but when it comes to cloud connectivity you will be using BGP. Why not OSPF or EIGRP? These protocols rely on IP broadcast or multicast to find neighbor routers and form peering adjacencies, and are generally intended for use within a LAN. BGP peering is established using TCP, and it was designed to operate over a WAN or the Internet. It is, in fact, the duct tape and baling wire that holds the internet together!

BGP requires a few bits of information to get working. First, you will need to enable the BGP process on your router and assign an Autonomous System Number (ASN), which will be explained in the next section. Next, you will define which networks will be advertised by BGP. The final step is to configure a neighbor router to peer with, along with the ASN of that router. Once the peering relationship is formed, your router receives all of the known BGP routes from the neighbor.

In some cases, BGP relies on another routing protocol to be able to operate. When a router tries to establish a peering relationship, the TCP packets it sends need to be able to make it to the intended neighbor router. When using BGP to connect to the cloud, the routers involved are typically assigned addresses from within a /30 (or /31) subnet. This means no routing is required for the two devices to communicate – they are both connected to the same subnet and can communicate directly. Whether this communication happens over an IPsec tunnel or a point-to-point circuit doesn’t really matter, as long as the two devices can talk to each other.

The magic happens when BGP peering is established over multiple paths to the same destination, which is what provides both redundancy and resiliency. We’ll get into the details in a moment, but this the way we can automatically failover if one link goes down. BGP will see the destination subnets advertised from multiple neighbors, and it will pick which path is the “best” based on an algorithm. If a circuit goes down and the neighbor is no longer reachable, BGP will choose the next best path, and traffic will be forwarded accordingly. These paths can be the same type of connection, or different. Here are a few examples:

- Redundant, route-based IPSec VPNs. Route-based VPNs allow BGP peering across them, providing a failover method if one tunnel fails.

- A combination of a direct connection and a route-based VPN as a backup

- Multiple direct connections

If you’re using a solution like Megaport for connectivity, their website has several example network diagrams for redundant connectivity.

Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs)

BGP uses the term “Autonomous System” to represent an entity or location, and each autonomous system is assigned a number (ASN). There are a few different flavors of ASNs, but for our purpose, we only need to worry about public and private ASNs. Much like IP addresses, public ASNs must be assigned by a regional internet registry (RIR), while private ASNs (64512-65535) can be used freely within a private network. Each ASN in the routing topology must be unique, so you will need to plan your ASN usage to prevent overlaps, just as you would with your IP ranges. In some cases, a cloud provider will allow you to specify a private ASN for your cloud resources, and in other cases, it is set by the provider and cannot be changed. Check your cloud provider’s documentation to see what ASN they use so you can plan accordingly. If you have been assigned a public ASN then your life is a bit easier, since it is unique to your organization. Some commonly used ASNs are listed below.

| Cloud Provider | ASN | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AWS | 7224 64512 |

ASN 7442 is used for Direct Connect peering. ASN 64512 is the default ASN for VGW or Direct ConnectGateway, but you can specify a different private ASN when those resources are created. |

| Azure | 8074 8075 12076 65515-65520 |

ASN 12075 is used for ExpresssRoute peering. ASNs 65515-65520 are reserved by Azure and should not be used on the customer side. |

| GCP | 16550 | ASN 16650 is used for Interconnect peering. |

| Oracle | 31898 64555 |

ASN 31898 is used for Private and Public peering. ASN 64555 is reserved by Oracle and should not be used on the customer side. |

| 23456 429496729 64496-64511 65535-65551 | These ASNs are reserved by IANA and should not be used on the customer side. |

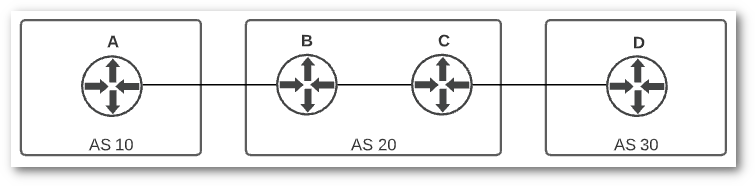

Each route that BGP learns also includes the AS Path needed to reach that destination. The path is the list of ASNs that are traversed to reach the destination. Consider this diagram:

The AS path from router A to router D is 20 30. Likewise, the AS path from router D to router A is 20 10. The AS path is an important part of the algorithm BGP uses to choose the best path to a destination, which we will learn more about in a moment. It is also used to prevent loops. If a BGP router receives a route with its own AS in the path, the route is discarded as a loop-prevention mechanism.

Internal BGP (iBGP) vs External BGP (eBGP)

I’m not going to get too in-depth on the inner workings of BGP, but it is worth knowing the difference between internal BGP (iBGP) and external BGP (eBGP). iBGP is the term for BGP peering between two routers within the same autonomous system. eBGP is the term for peering between two different autonomous systems. In the example diagram above, routers B and C are connected via iBGP, and the remaining connections are eBGP. Connections to a cloud provider will always use eBGP. If you are running iBGP within your network, then there is a good chance you already know more about BGP than I’m going to cover in this post!

BGP Best Path Algorithm

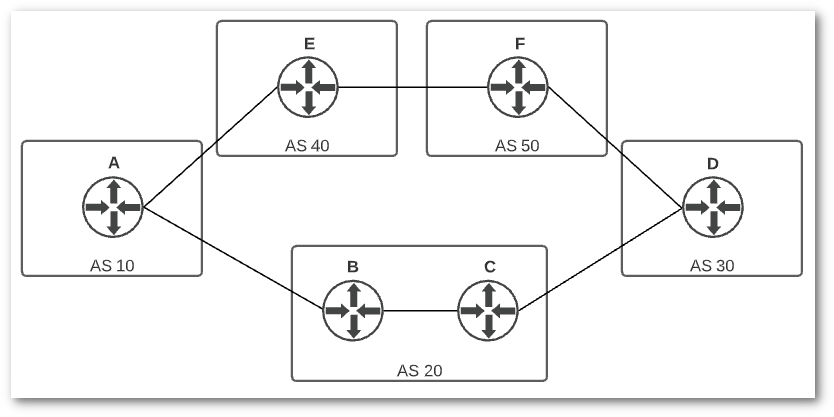

If you’ve ever studied for a CCNA, you may get cold chills reading the phrase “BGP Best Path Algorithm”. Immediately your brain recalls the “N WLLA OMNI” acronym used to remember the steps in the algorithm, although you may struggle to remember what the letters stand for. For our purposes, the primary metric we need to worry about is the “A” – AS path length. As long as the other metrics are equal, which they typically are, BGP simply counts the number of autonomous systems it has to traverse to reach a destination to determine the AS path length. The path with the least number of autonomous systems traversed is considered the best path. Whether or not this path is the best performing or least latent is another question altogether, but these are not metrics that BGP considers as part of its algorithm. Here is another example topology to consider:

There are now two paths from router A to router D, 20 30 and 40 50 30. The latter may be higher bandwidth or more reliable, but BGP will pick the path through AS 20 since that will result in the shortest AS Path (20 30).

One tool that can be used to influence BGP path selection is AS prepending. AS prepending means you artificially add additional AS numbers into the path. These prepending rules are applied to a neighbor relationship between routers and should use the ASN of the local system. Prepending an ASN other than your own may have unintended consequences. AS prepending may be performed outbound on routes being advertised to neighbors or inbound on routes being received from neighbors.

Here is an example to illustrate this concept. If router D (AS 30) prefers traffic from router A (AS 10) to arrive over the link with router F (AS 50), it can prepend 30 30 to the AS path it advertises to router C (AS 20). This new path will be advertised to router A, and the two paths router A will see to router D are 20 30 30 30 and 40 50 30. Now, the best path is through AS 40 and 50, since it is a shorter AS path. Using AS prepending is a way to influence the routing topology to behave differently from the default BGP behavior. You will frequently see this practice referred to as “traffic engineering”, although AS prepending is just one of many tools available to manipulate BGP.

Equal Cost Multipath (ECMP)

By default, BGP will calculate a single path to each destination. As I mentioned earlier, that path may change if a failure happens somewhere in the network, which is exactly what we want to see. But what about the scenario where we have two high bandwidth links to a destination? It may feel like a waste of money to have an expensive circuit provisioned to merely serve as a backup. This is where Equal Cost Multipath (ECMP) comes in. ECMP allows for two or more “equal cost” routes to be installed in the routing table. ECMP is used frequently in networking to leverage multiple links at the same time, but different routing protocols handle it differently. There may even be differences in behavior between hardware vendors. Generally with BGP, ECMP has to be enabled, so refer to the vendor documentation to figure out the right knob to turn.

When properly configured, ECMP will allow you to take full advantage of the available links. A common scenario is two direct connections to a cloud provider (ideally purchased from two different carriers for diversity). When both links are working, traffic is transferred across either link based on a “hash”. Usually this is done by reading the source and destination addresses and port numbers of a packet and feeding them into a predefined calculation to produce a hash value. Even values would be assigned to one link, and odd to the other, providing a rudimentary way of balancing traffic across the links. If one circuit fails, that route is removed from the routing table, and all traffic would traverse the remaining link. Redundant and cost-effective!

Additional Considerations

By now you’ve probably read all you care to about BGP, but there are a few more components I’d like to mention.

- Bi-directional Forwarding Detection (BFD) is a network protocol that is complimentary to BGP. By default, BGP can take several seconds or minutes to detect a failure. BFD can be used to speed up failure detection. If you cannot tolerate an outage of more than a few seconds, configure BFD along with BGP.

- Prefix lists define a list of routes, and they can be used to filter the routes that are either advertised or received by BGP. Applying prefix lists to your BGP neighbors is a best practice. By default, your equipment will receive all routes advertised by its BGP neighbors, and you certainly want to prevent unintended routes from being advertised into your network. Refer to your network vendor documentation for prefix-list syntax and application.

- BGP peering over a public network can be a security risk since attackers could use the advertised routing information to perform reconnaissance on your network. To mitigate this, BGP peering can be encrypted with a pre-shared authentication key. This is also considered a best practice, and you will need to read the docs to determine how this is configured on your equipment. To prevent unnecessary troubleshooting, I typically try to stand up a BGP peering connection without authentication. I’ll go back and enable authentication once I’ve confirmed it’s working as expected.

Wrap Up

Multiple redundant links with automated failover is your goal if you want reliable connectivity to the cloud. If it’s up to me, I’m using SD-WAN everywhere that I can. All of the complicated bits of BGP are abstracted away, leaving only the benefits. There is always a trade-off, which in this case is vendor lock-in, and perhaps cost depending on how large your network is. But BGP has been around for a long time, and it’s not going anywhere. There are plenty of network engineers who have spent hundreds of hours designing and supporting BGP, so you will seldom have to worry about finding someone that can provide support for your environment. Chose the solution that works best for you, plan, design, deploy, test, and test again. If everything goes as planned, you will have rock-solid connectivity to the cloud of your choice.